Works

The Interactive map of the main works

Following the points of the map

Works inside the Duomo

Interactive map

Mater Consolationis

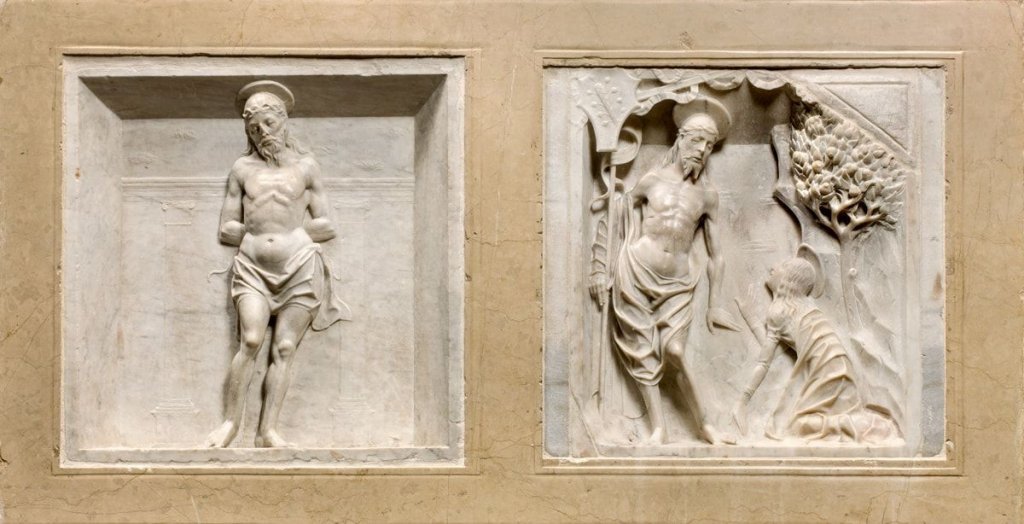

Mater Consolationis 11) Christ at the column | Noli me tangere

11) Christ at the column | Noli me tangere 10) St Francis stigmatized | A penitent Saint Jerome

10) St Francis stigmatized | A penitent Saint Jerome The great Cross

The great CrossToday it is located in the Diocesan Museum

Conversion of Saul

Conversion of SaulNorth transept, central nave, wall opposite the façade

Mater Boni Consilii

Mater Boni Consilii Head of HolofernesChapel of the Our Lady of the People - detail of the statue of Judith

Head of HolofernesChapel of the Our Lady of the People - detail of the statue of Judith Head of John the Baptist

Head of John the Baptist Jesus Christ Crucified

Jesus Christ CrucifiedToday it is located in the Diocesan Museum

Madonna Fodri

Madonna FodriThe donor Benedetto Fodri is depicted at the feet of the Madonna with Child

St. Himerius distributes alms

St. Himerius distributes alms Triptych of St. NicholasMarble triptych of St. Nicholas of Bari between the Sts. Damian and Homobonus; in the coping, Christ in the sepulchre

Triptych of St. NicholasMarble triptych of St. Nicholas of Bari between the Sts. Damian and Homobonus; in the coping, Christ in the sepulchre Funeral monument by Sfrondati

Funeral monument by Sfrondati Triumph of Mardocheo

Triumph of MardocheoSouth transept, central nave, wall opposite the façade

Angel of the AnnunciationBuilt as an organ door in the Baptistery.

Angel of the AnnunciationBuilt as an organ door in the Baptistery.Today it is located in the Diocesan Museum

Mary at The Annunciationbuilt as an organ door in the Baptistery.

Mary at The Annunciationbuilt as an organ door in the Baptistery.Today it is located in the Diocesan Museum

The expressive force that is hidden in marble is always surprising and looking at the two pulpits that adorn the main nave, one cannot but be impressed by the excellent quality of the reliefs that can be admired.

Designed by the architect Luigi Voghera between 1813 and 1817, the two pulpits preserve some of the most precious examples of Renaissance sculpture of the Lombardy area: the eight panels depicting the episodes of the Martyrdom of Saints Mario, Marta, Audiface, and Abacone (Marius, Martha, Audifax, and Abachum). In the left pulpit: The Martyrs before the emperor, The Sentencing, The Flagellation, The Stake;in the right pulpit: The cutting off of the hands, The Decapitation of Mario, Audiface and Abacone, The corpses at the stake and The Martyrdom of Martha. It is a group of reliefs in white Carrara marble purchased in 1805 together with four small columns and some decorative elements by the Vestry Committee of the Cathedral near the heirs of the Meli family and coming from the disassembled “Ark of the Persian Martyrs”, already in San Lorenzo: one of the most emblematic funerary monuments of the Lombard Renaissance. Commissioned in March 1479 by AntonioMeli, the abbot of the Benedictine monastery of San Lorenzo, to the Milanese sculptor Giovanni Antonio Piatti, who should have completed the work by Easter 1481; the arch will actually see the light thanks to the conclusive intervention of another great sculptor: Giovanni Antonio Amadeo. In fact, both Meli (in August 1479) and the Piatti died(in February 1480), following a prearranged agreement between the two artists; it is precisely Amadeo who assumes the task of completing the work to the point of affixing his own signature, in this way attributing to himself every merit and every effort and thus also succeeding in opening up a new path towards important future Cremona commissions.

The attribution of the enchanting tiles, given the alternation of the artists who worked with them, has always been controversial, but the style that the reliefs present seems to point to Piatti, both for the rigorous line of the design, both for the perspective style that characterizes them – of which Piatti is an undisputed pioneer, both for the geometric and almost “paper” effect of the drapery; elements, as a whole, that hardly recall the expressive modalities of Amadeo, whose compositions instead are dramatic. Hence in the short period that precedes his death, Piatti has already set these eight tiles and also executed other sculptures that constituted the decorative apparatus of the arch, including The Virgin and Child (purchased from the Edmond Foulc Collection by the Philadelphia Museum of Art), a Saint Benedict and a Sain Lawrence (Kneeling Cleric Holding Mitre and Cleric with Book, respectively, both now in the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art in the Sarasota, Florida).

Amadeo, with the collaboration of his workshop, thus dealt with the final adjustment of the reliefs and the installation of the arch, but his cunning in attributing the entire work to himself without recognizing the merits of his distinguished colleague allowed him to receive other prestigious assignments such as the construction of the arches of St. Himerius (Sant’Imerio) and St. Arealdo (Sant’Arealdo), both completed in 1484. Of the first we can still admire the splendid “picture” – the only element that has survived up to today – now walled up into the entrance wall of the presbytery towards the southern transept, depicting St. Himerius who distributes alms: a work that demonstrates the full maturity of an artist who knew how to bring to the maximum expression what he had been able to absorb from a Master like Piatti, in a relief where the perspective setting and the compositional complexity reach an optimal level. Of the St. Arealdo arch we can still admire a panel found in the center of the front side of the arch of Saints Marcellinus and Peter (Marcellino and Pietro), in the crypt depicting the Ecce Homo and four others walled into the counter-façade of the northern transept (Christ at the column, Noli me tangere, a stigmatized St. Francis, a penitent St. Jerome).

Stones that artists of unquestionable value have been able to sculpt, smooth, thus searching and disclosing their most hidden soul, creating works of an extraordinary quality whose beauty, pure and unadulterated as the marble from which they were generated: timeless.

Among the treasures of fine goldsmithing in the Cathedral, the Grande Croce (Great Cross) is the most representative masterpiece of the Lombard goldsmiths of the fifteenth century, in terms of architectural structure and dimension. Wanted by the Massari- a lay group that constituted the so-called Fabbrica del Duomo – as a decor of the main altar for the major solemnities of theliturgical year, the cross is the work of goldsmiths Ambrogio Pozzi of Milan and Agostino Sacchi of Cremona. Roughly three meters high, it was crafted between 1470 and 1478, and made of silver, gold, cobalt enamel and lapis lazuli; it consists of a refined assembly of over a thousand pieces and presents a virtual gathering of 160 small and large statues, with 50 busts of saints.

In an interpretation that is not limited to stylistic appreciation, the Great Cross reveals an genuine exaltation of the Mystery of Redemption that is renewed every day on the altar; hence, in addition to Calvary proper (the crucifix flanked by the Virgin and by the Apostle Saint John), we admire its first germ in the Mystery of the Incarnation (the Eternal Father, the Annunciation and the Archangel Gabriel, in the octagonal niches), the prophets its vaticinators (David; Isaiah; Jeremiah; Ezekiel; Daniel; Zachariah), the Evangelists its descriptors (Matthew; Mark; Luke; John), its best known symbols (the pelican; the tree of life), up to the final triumph of the risen Christ at the peak. In the crown of the Saints we find Cremona’s Homobonus, Himerius, Marcellinus and Peter the Exorcist, as well as Milan’s Ambrose, Babylas, Vittore, Arealdo, in addition to many others.

In the center, on the back of the work, is the Virgin of the Assumption to whom the Cathedral is dedicated.

The monumental base, in silver, gilded in some parts and in lapis lazuli is an eighteenth-century work (1775) carried out by the silversmith Giuseppe Berselli following a design by the architect Giovanni B. Manfredini, both from Cremona, and is adorned with statues representing the Virtues and a crown of eight sorrowing angels holding the instruments of the Passion.

It is a exquisite example of goldsmith’s art that truly amazes for its grandeur and as well as its refinement.

Visit the side Chapels

Explore the interactive maps